.

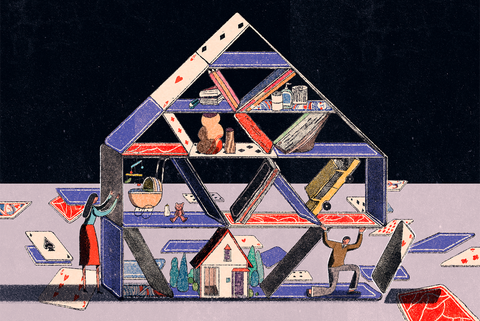

IT’S 7:15 ON A TUESDAY night and I’m neatly folding my wife’s underwear. This is not something I usually do. This is not something I usually want to do. But right now, in the name of domestic serenity, and quite possibly for the sake of our family, I am gingerly doubling over each pair of panties and tucking them into her top drawer. My wife is putting our toddler to bed and I’m thinking to myself, well, this is weird.

This all started when my wife called me out on my parenting abilities during a family vacation. She recounted how, at a brewery earlier in the day, I had watched as our son picked up two mason jars filled with crayons and began banging them together. “You just kind of stood there. Like you weren’t worried he might shatter them and hurt himself,” Meghan said.

I admitted to her that I hadn’t thought that might happen. It was like previous times, when I’d let our son get dangerously close to an exposed wall outlet or lamp cord and my wife had to jump in to rescue him. I didn’t know it at the time, but I’d been relying on Meghan to do more than her fair share of mental labor—those household tasks that demand vast stores of cognitive energy—on my behalf.

.

“If this isn’t something we can fix, I’m not sure I’ll ever want to have another kid,” she said.

If my own wife couldn’t trust me with our child, then perhaps I had to become better at undertaking those mentally demanding jobs—like watching our son closely so that he doesn’t accidentally shock himself.

The prospect of another kid wasn’t the only thing at risk. Women who felt that they bore the majority of the mental labor inherent in running a household were also likelier to feel empty, less satisfied with life, and less emotionally and physically intimate with their partners, Oklahoma State University and Arizona State University researchers found this year.

On top of all this mental labor, women are doing the majority of the chores, despite the fact that more of them have jobs. In 1965, women spent on average 42 hours a week on chores and childcare and nine hours on paid work. In 2016, they spent 32 hours a week on those domestic duties and almost tripled their paid work hours. Men today, by comparison, spend 43 hours a week on paid work and only 18 on housework and childcare.

You could fool yourself into thinking that, well, men spend more time at work, so they’ve earned their time off. Except that most breadwinning mothers report that they handle all (not some) of the family’s responsibilities, according to a 2017 survey by the childcare company Bright Horizons. While men might be doing slightly more housework than they were in the 1960s, we’re not doing nearly enough—and it’s breaking our partners.

.

And something happens when men become fathers. A 2015 study published in the Journal of Marriage and Family found that in heterosexual marriages in which the couple reported sharing the domestic workload pre-child, the man went on to decrease his housework contributions by as much as five hours a week after the child was born. The wife picked up his slack, and all that slack amounted to 2.6 extra weeks of work for her over the course of a year. One explanation: Babies upend the dynamic that couples have and, as parents, they default to the domestic roles they grew up with.

So, for instance, if your dad didn’t do the laundry in your house growing up, you’ll likely follow suit.

Which brings me back to folding my wife’s underwear.

.

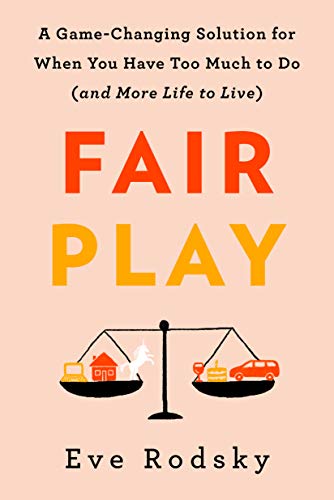

A WEEK EARLIER, Meghan and I had agreed to follow the rules of a new book, Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live). The Fair Play system was devised by Eve Rodsky, an organizational specialist with mediation experience. She argues that in order for women to avoid being the “She-Fault” parent, they must create equity in household chores, or else risk frustration, resentment, and divorce.

She also argues that to achieve this equity, they must participate in the Fair Play “game,” which centers on a deck of 100 cards. Thirty of these cards deal with what you’d expect—doing dishes, taking out the garbage, handling the mail. There are 54 other cards devoted to chores that occur less frequently (thank-you notes, health insurance, lawn and plants). The remaining 16 cards are divided into ten wild cards (moving, new job, death in the family) and six happiness-centric cards (adult friendships, self-care). The goal is not to carry an equal number of cards but to feel like the responsibilities each person holds are fair and reasonable.

“Is this a ruse to get me to do more cooking?” Meghan asked when we sat at our kitchen table for our first summit. Going into it, I felt like I may have had the higher ground: I do all of the cooking for our family, and the yard work, and most of the nasty cleaning, dishes, grocery shopping, and holiday-related stuff. Because I work from home, my daily breaks involve household chores—and a good number of them. Although I calmly reassured Meghan that, no, this project wasn’t intended to unload my responsibilities onto her, I was hoping that maybe it would.

.

But as we divvied up which responsibilities we would each handle for the week ahead, I noticed that while Meghan and I held roughly the same number of cards, the type of cards differed. I held the majority of the cards that required physical labor. Meghan held the majority of the cards that required mental labor—cards like “calendar keeper,” “money manager,” and “medical and healthy living (kids).” Wanting to retain my perceived footing on higher ground, I asked Meghan for the “local packing and unpacking” card, which entailed stocking the diaper bag for outings around town. It seemed like an easy one.

My father did more around the house than I think most dads did, but I can guarantee you he never held the “local packing and unpacking” card. My mom did that, and we always had what we needed. This is what my wife did, too.

Until it was my turn.

During the opening weeks of Fair Play, we were invited to a family friend’s pool. I packed the sunscreen, my son’s swim diaper, a few pool toys, his water cup, and what else, what else—I thought that was good. Two blocks from home, I realized I’d forgotten his pool float. I turned the car around to pick it up; I delivered him to the pool, where he had a ton of fun; and afterward I suggested we all go out for dinner. Then I realized I hadn’t packed him a change of clothes.

.

How could I have failed so poorly at something so simple? I wondered. I began to understand: Mentally mapping out exactly what a super-needy kid will require for four hours is daunting. In fact, it’s emotionally exhausting to prepare for all the scenarios, including the worst ones, and especially if it’s a habit you’ve never seen practiced or practiced yourself.

Meghan and I returned home that night to find I wasn’t the only one struggling with our new division of labor. A squadron of flies had stormed our kitchen, likely bursting forth from the fetidness of the trash can. Meghan held the “trash” card. “Maybe they’re coming from outside?” she pondered.

.

OVER THE NEXT MONTH, Meghan and I discussed our domestic life ad nauseam. For as convoluted and overwhelming as the Fair Play system is, it does force you to have difficult conversations. About what it means to truly execute a task. About what your agreed-upon minimum standard of care is. About competency and consistency and, all along in the background, the by-product of those two things: trust.

Trust is earned, and it is earned in a “trust spiral,” a phrase coined by Sibout G. Nooteboom, Ph.D., a public administration researcher at Erasmus University Rotterdam. Positive trust spirals grow from a repeated sequence: establishing a common goal, having enthusiasm, navigating tensions to reach the goal, and reward. Negative trust spirals feed off the opposite.

.

“Helping” in the form of nagging or swooping in to finish the job does not feed trust, Rodsky says. In fact, the Fair Play system discourages helping. If one does the laundry, one does all of the laundry. This includes deciding when to do laundry, doing the laundry, folding the laundry, and putting away the laundry.

“When you hold a card, you own it. You conceive, plan, and execute. And your partner isn’t allowed to give feedback in the moment. That’s saved for weekly meetings,” Rodsky says. And while she describes her plan as “hardcore change from how things are done currently,” she argues that anyone who has ever had a job understands what it means to take on a task and complete it. “Every business works on a direct-responsibility model. Why shouldn’t the household?”

Before Fair Play, I was routinely miffed at my wife for not taking out the garbage as much as I did, without ever giving her full responsibility to do so. My wife was routinely miffed at me for not watching our son as closely as she would have, without ever entrusting me to carry out the full responsibility of what that means.

.

I kept coming back to that vacation fight my wife and I had—to the mason jars and what they represented to her. She wasn’t just asking me to watch our son when we were out in public. She was asking me to handle the mental responsibility of making sure he was safe, so that she could be comfortable.

At our week-three summit, knowing that we’d be attending a birthday party for our friends’ two-year-old son that weekend, I took the “watching” card and actually brought it with me to the party. Carrying around Fair Play cards isn’t required, but I deemed it necessary for the task at hand. I traded “watching” with Meghan exactly once, when I needed to eat, but otherwise hovered over my son as he splashed at a water table, pushed a toy lawnmower, shoveled a god-awful amount of fruit into his mouth, and meowed at cats. Two hours in, I was spent.

After the party, Meghan told me, “You’re more competent than I give you credit for.” I took it as a compliment.

.

DURING OUR LAST SUMMIT, I asked Meghan if she was ready to burn our cards in a ceremonial bonfire. After our usual griping about the madness of the system, we decided instead to reduce our load to just a few key cards that served as trouble spots for us—“packing and unpacking,” “weekend meals,” and “watching” included.

.

We were starting to build something, to trust-spiral upward, and we weren’t quite sure that our work was finished. But we both decided that we didn’t want to run our home like a business, because, well, home is a respite from business. Though Meghan did say, “Maybe we’ll bring the full deck of cards back if we have a second kid.”

I had always followed the advice of my hero, Tom Waits, when it came to marriage. When reporters have asked him the secret of his long marriage to Kathleen Brennan, he’s replied, in reference to doing dishes, “She washes, I’ll dry.” I had always assumed that meant splitting the work 50/50, but now I understand that true synergy in a relationship comes from each partner holding an equitable—not equal—share of physical and mental chores. No woman should carry the mental weight of childcare. No man should bear the load of labor tasks. And vice versa.

In the end, my wife actually did start cooking more, on weekends, so that I could devote more mental energy holding on to that damn “packing and unpacking” card. I wash and I dry so she can keep the calendar. We take turns watching. And I do the laundry. I’m even starting to enjoy folding her underwear.

Source: Read Full Article