As countries emerge from lockdowns imposed to blunt the coronavirus pandemic, dozens have rolled out phone apps to track a person’s movements and who they come into contact with, giving officials a vital tool for limiting contagion risks.

The technology could help avert new surges in COVID-19 infections that might overwhelm hospitals battling an outbreak that has killed more than 350,000 people worldwide in just six months.

While many apps and related technologies are voluntary, other governments are enforcing their use, since health experts say at least 60 percent of a population needs to activate them for contact tracing to be effective.

But privacy advocates warn they give unprecedented access to personal data that could be exploited by authorities or even third parties, despite pledges that information will be kept out of reach.

The stakes are high, since only a small percentage of populations in many regions have been infected by the new coronavirus, meaning huge numbers of people are still at risk of infection.

Here is a rundown of the different approaches adopted since the first COVID-19 cases were reported in China last December, and what officials have learned from their experiences.

Asia

Asian countries were the first to roll out tracing apps, with China launching several that use either direct geolocalisation via cellphone networks, or data compiled from train and airline travel or highway checkpoints.

Their use was systematic and compulsory, and played a key role in allowing Beijing to lift regional lockdowns and halt contagions starting in April.

People are ranked green, yellow or red based on their travel history and exposure to infected people, to determine if they can travel or enter public areas.

South Korea, for its part, issued mass cellphone alerts announcing locations visited by infected patients, and ordered a tracking app installed on the phone of anyone ordered into isolation—aggressive measures that helped limit deaths to just a couple of hundred in a population of 51 million.

In Hong Kong and Taiwan, which have managed to limit deaths despite their proximity to China, officials use GPS and Wi-Fi to keep strict tabs on people in quarantine.

But most other countries turned to bluetooth tracking via apps that remain voluntary and let authorities “see” when two people’s devices come into close contact.

Officials say actual identities are encrypted, and anyone receiving an alert will not know who posed the potential contagion threat, but those pledges have failed to reassure many.

Australia’s COVIDSafe app, rolled out in April, has been downloaded 6.1 million times by its roughly 15 million smartphone users, though there is no data on how many remain active daily.

India’s government launched the Aarogya Setu (“Bridge to Health”) app, with more than 100 million downloads since April—less than one-tenth of its population, since only one in four Indians owns a smartphone.

In Iran, home to the deadliest outbreak in the Middle East, the Mask app is being pushed by officials, though rights groups say the government could be tempted by surveillance possibilities after months of unrest.

Pakistan, for its part, has tapped its powerful intelligence services to deploy secretive surveillance technology normally used to locate insurgents to track coronavirus patients and the people they come into contact with.

Europe

Concerns about privacy protections are particularly acute in Europe, where officials have called for collaborative efforts that would include intense oversight to make sure users know when and how personal data is being exploited.

A nonprofit coalition, Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT), was set up to offer technologies for building apps, though in many cases governments have struck out on their own.

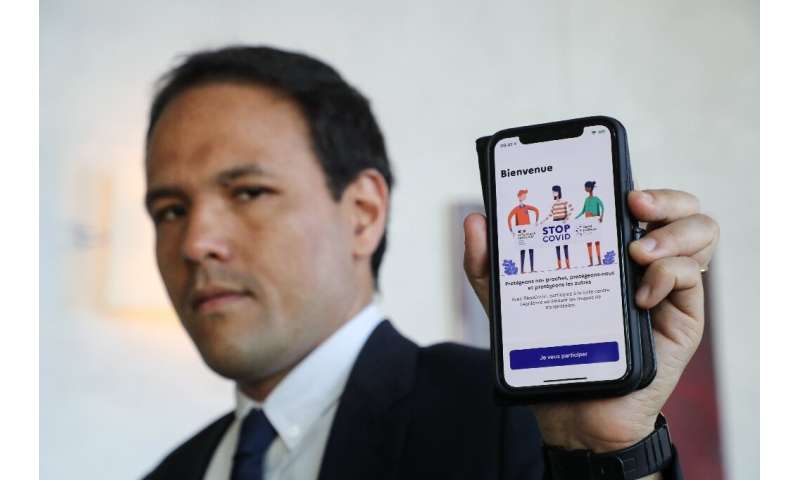

France, for example, will launch next week a voluntary bluetooth-tracing app that it says will not disclose any personal information, with records erased once the crisis is over.

But the government declined to work with either Apple or Google, which have teamed up to give tracing app developers a way for phones to communicate across their separate iPhone and Android operating systems.

Britain’s National Health Service is also developing its own system, which is still undergoing testing. In the meantime it is relying on manual tracing, mobilizing 25,000 people to contact people who test positive.

Germany and Italy opted to use the Apple-Google venture for apps to be rolled out in the coming weeks, as have Austria, Ireland and Switzerland.

Several other countries are rolling out apps as well, but Belgium and Greece remain reluctant because of fears officials and companies could be tempted to compile huge databases on people’s movements and activities.

Spain has also held back on a national app so far, though Madrid and some regions have introduced them.

Sweden has also rejected a tracking app, despite having more COVID-19 cases than in neighboring countries like Denmark and Finland, which plan to have tracking apps operational in the coming weeks.

Middle East

A number of Gulf countries including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Bahrain have rolled out bluetooth tracing apps—Doha has even made its use mandatory, warning that violators face up to three years in jail, prompting a rare backlash over privacy concerns.

Israel’s health service in March launched the Hamagen app, Hebrew for “the Shield,” which uses a phone’s GPS data and is available in five languages.

But the Israeli government also allowed the Shin Bet spy agency to monitor people’s phones under emergency powers, a move decried by rights groups who warned of an irrevocable setback to privacy safeguards.

This week, lawmakers extended the controversial measure until June 16, but only in “individual and unique cases.”

In Egypt, officials began urging people to use an app that sends alerts of areas with potential coronavirus contagion, though it remains unclear how many people are using it.

Americas

In the United States, there is no national tracing plan under consideration, but some states have announced their own, either for bluetooth apps or, in the case of Hawaii, sending out daily questionnaires via text and email to help build a database to track infections.

Just three US states (Alabama, North Dakota and South Carolina) say they have adopted the Apple-Google technology, while other states have developed their own systems, such as Rhode Island’s “Crush Covid” app, which gathers GPS data.

Canada has declined to offer a tracing app so far, though the province of Alberta has its own app, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said his government is studying a national app that would address privacy concerns.

In Mexico, only a handful of privately developed apps have emerged, alongside one from the state of Jalisco.

Source: Read Full Article