The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to persist as a result of the spread of newer variants of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). To date, several vaccines have been administered around the world at record volume and speed in an effort to achieve herd immunity and ultimately restrict the spread of the virus.

However, vaccine hesitancy is proving a formidable barrier to this goal. In simple terms, having an effective vaccine does not equate to widespread acceptance of the vaccine. A recent study published on the preprint server medRxiv* discusses vaccine hesitancy in India, which is one of the most populous countries in the world. This nation is seeing high vaccination rates overall, coupled with resistance to the vaccines in various regions.

Study: COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in India: An Exploratory Analysis. Image Credit: Manoej Paateel / Shutterstock.com

Study: COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in India: An Exploratory Analysis. Image Credit: Manoej Paateel / Shutterstock.com

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy defines vaccine hesitancy as the “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination, despite availability of vaccination services.” In order to achieve success in the Indian vaccination program against COVID-19, the barriers that exist to vaccination, whether related to mental or logistical issues, must be identified and overcome, as far as possible.

Many researchers have examined this problem in high income countries (HICs), bringing out models such as 5Cs to explain vaccine hesitancy and 5As to foster vaccine acceptance. Comparatively, the corresponding efforts in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are lacking. Such research is therefore crucial to ensure that vaccine uptake reaches optimal levels in the current pandemic.

The lowest levels of vaccine coverage at present are in LMICs due to supply shortages coupled with vaccine hesitancy. In India, however, both homegrown and foreign vaccines were being manufactured even before formal approval processes were completed. This is reflected in the relatively higher degree of vaccine uptake in India among LMICs.

Nonetheless, the vaccine rollout in India has not been as rapid as intended. Thus, lessons on vaccine hesitancy from this country may help to guide future campaigns here and abroad.

Earlier instances of anti-vaccination sentiments in India occurred in relation to the polio vaccine, localized to some districts in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, both among the states with high illiteracy and poverty rates, and the Hemophilus influenza B (Hib) vaccine in 2010.

Vaccination in India is associated with childhood immunization, thanks to the Universal Immunization Program (UIP) set up in the 1970s. As such, adult immunization is a relatively new and foreign concept, except for the ubiquitous tetanus toxoid shot. This state of affairs may have led to some hesitancy as well.

The psychological, social, and political aspects of a mass adult vaccination program against a new disease have not yet been evaluated, which may have contributed to the lack of trust being seen in some parts of the country.

The COVID-19 vaccination program began on January 16, 2021, with the Covishield adenovirus vector vaccine from AstraZeneca and the Covaxin whole inactivated virus vaccine from Bharat Biotech. The first to receive the vaccine were frontline workers, such as health workers and security staff, who have extensive contacts with the public. This phase lasted until February 28, 2021.

From March onwards, all individuals aged 60 years or above were eligible for the vaccine, as well as those aged 45 years or more who had underlying health conditions, such as diabetes, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or high blood pressure. The third phase began in April 2021, when the vaccine was opened up to all people above 45 years. Finally, from May 1, 2021, anyone above the age of 18 years became eligible.

COVID-19 vaccination in India is deemed to be voluntary in all cases, which has been associated with delays in vaccination despite the vaccine being available.

Study findings

The researchers found that about 60% of Indians are hesitant to take the COVID-19 vaccines overall. The extent of hesitancy varies between places, being higher in rural areas. Vaccine uptake was low and declining during the third and the initial part of the fourth phase of vaccination.

The reasons for this vaccine hesitancy may be vaccine shortage, lack of willingness, or barriers to vaccination such as lockdowns in various places, or high infection rates predisposing to a fear of visiting hospitals and other vaccination centers, during the peak of the deadly second wave that began in April 2021.

Another possibility is the myth that the vaccines caused death rather than preventing COVID-19. The first and second phases of the vaccination campaign targeted the most vulnerable groups of the elderly and those with other health conditions. These individuals were the hardest hit during the second wave.

Since many of these individuals had received the first dose of either of the two vaccines used in India before they fell ill, and died, the story of the vaccine’s deadliness may have gained strength. The lack of knowledge of how prime-boost vaccine regimens work, as well as the poor immunity after a single dose, particularly in rural areas but also among many urban dwellers, provided fertile ground for such disinformation.

Yet another possible reason is that vaccine supply may have been heterogeneous, with urban areas cornering more of the vaccine stocks, leaving rural areas relatively unprotected against the second wave.

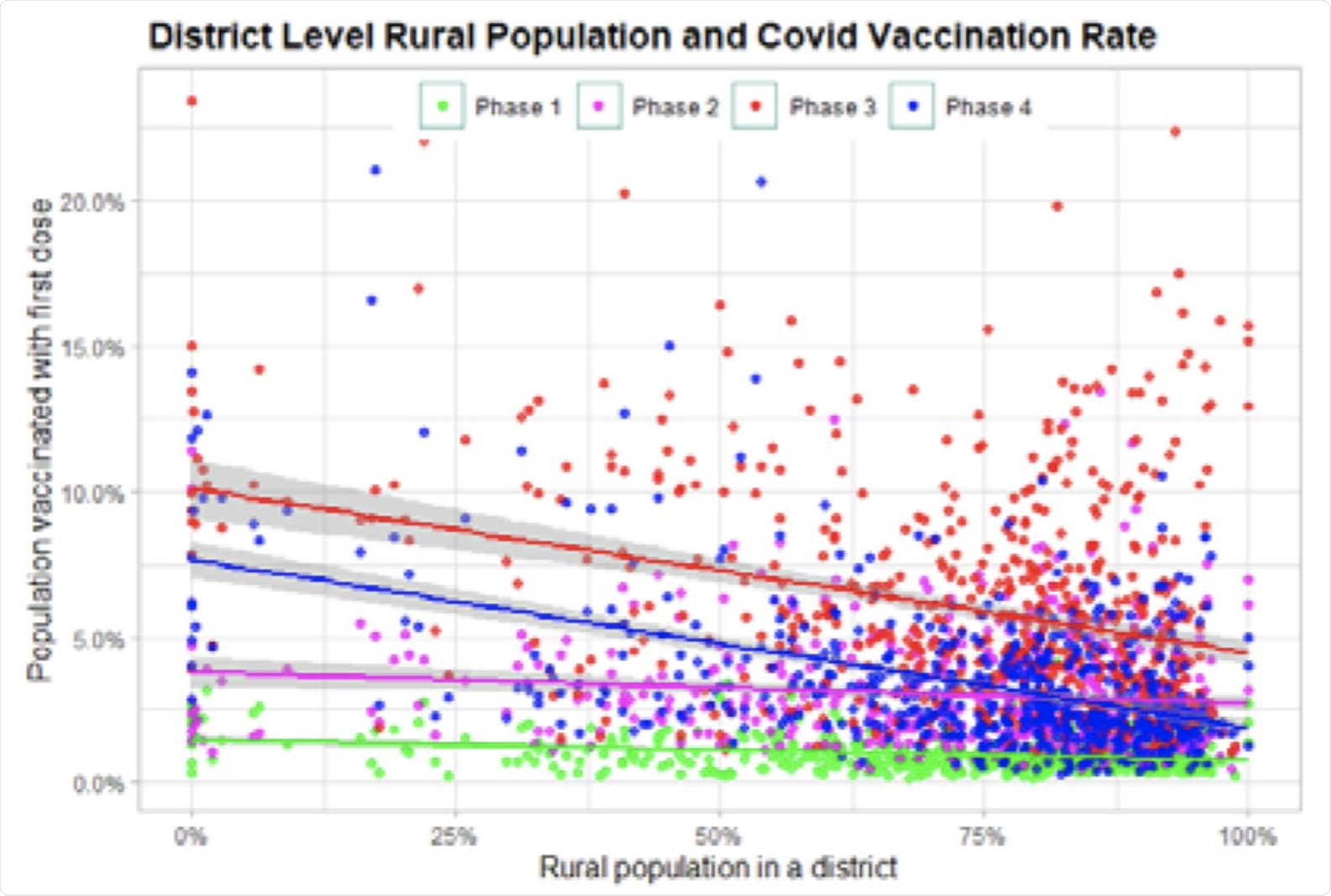

Rurality and vaccination rate.

Rurality and vaccination rate.

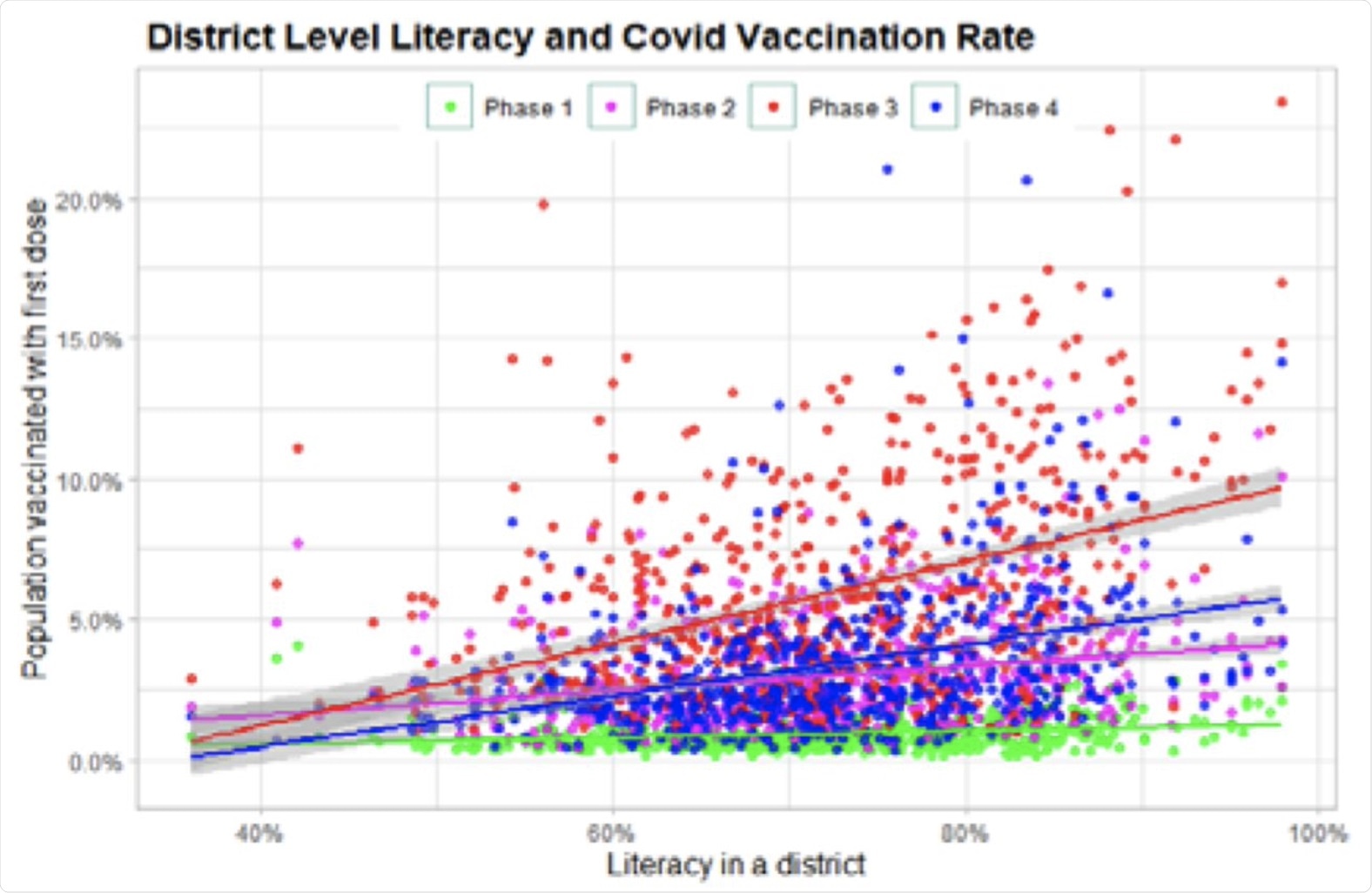

Literacy and vaccination rates.

Literacy and vaccination rates.

Vaccine uptake in India was far from uniform. Rural areas showed lower vaccine uptake than urban areas overall. The researchers looked at other indicators of healthcare acceptance, namely, childhood vaccine acceptance and family planning method acceptance.

They found that full childhood vaccination rates were highly predictive of COVID-19 vaccine uptake as well. While acceptance of family planning methods was not as closely correlated, the rates of female sterilization, which is by far the most common method practiced across India, was examined.

This showed a positive association, while the unmet need for family planning showed a negative correlation.

Implications

The study identified district-level trends in vaccination, correlating them with socioeconomic factors and health indicators. The high levels of vaccine hesitancy seen in India during the third and fourth phases were accompanied by increasing gaps in the vaccine uptake between different districts.

Comparing the rates of vaccination in the different phases can therefore help to identify regions with the highest levels of hesitancy. Most frontline workers were vaccinated early, probably because of the high risk they faced occupationally.

The rural-urban divide is not new but is most pronounced during the third and fourth phases. The urban areas experienced COVID-19 earlier, as well as being more aware of the disease and the vaccines. The rural areas, in contrast, were primarily hit during the second wave, which coincides with the third and fourth phases of vaccine rollout in India.

Linguistic barriers may have driven the relationship between illiteracy rates and vaccine hesitancy, as vaccine slots were booked online using an English-language app.

Again, marginalized communities such as the Scheduled Castes (SC), which may make up as much as half of the population in some districts, have historically had lower vaccination rates, and this was reflected in the current study. Districts with higher proportions of SC populations had lower vaccination rates up to the second month of the fourth phase.

In several districts, Muslim communities also showed significant vaccine hesitancy during the third phase, perhaps because it occurred during their Ramadan season when they fast from sun-up to sun-down. This may have led to religious fears that the vaccine might invalidate their fast, despite clarifications by Muslim clergy to the contrary, or that they might be unable to tolerate its side effects while fasting.

Importantly, this was not seen in several districts of Jammu and Kashmir, which has an over 90% Muslim population and had very high vaccine coverage. Similarly, Scheduled Tribes (ST) communities make up over 90% of the population in the North-eastern states, which also showed exceptional vaccine uptake. This may possibly relate to the active participation of such communities in public programs and governmental initiatives in these areas where they are in the majority, but not in other areas where they are socially and economically marginalized.

The relationship between child vaccination rates and COVID-19 vaccine uptake was positive, especially in the third phase when vaccine hesitancy was at its peak. This may mean that the latter is associated with a negative attitude towards vaccines in general. If so, it could help identify hotspots for vaccine hesitancy.

The study uses data on vaccination rates as a proxy for vaccine hesitancy, therefore ruling out shortages or inequalities in vaccine supply as a cause. Further research will be necessary to validate these conclusions, especially as COVID-19 vaccination for children is being considered.

*Important notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Agarwal, S. K. & Naha, M. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in India: An Exploratory Analysis. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.09.15.21263646. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.15.21263646v1.

Posted in: Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: Adenovirus, Blood, Blood Pressure, Children, Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, Diabetes, Fasting, Healthcare, High Blood Pressure, HIV, immunity, Immunization, Immunodeficiency, Influenza, Language, Pandemic, Polio, Poverty, Research, Respiratory, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Sterilization, Syndrome, Tetanus, Vaccine, Virus

Written by

Dr. Liji Thomas

Dr. Liji Thomas is an OB-GYN, who graduated from the Government Medical College, University of Calicut, Kerala, in 2001. Liji practiced as a full-time consultant in obstetrics/gynecology in a private hospital for a few years following her graduation. She has counseled hundreds of patients facing issues from pregnancy-related problems and infertility, and has been in charge of over 2,000 deliveries, striving always to achieve a normal delivery rather than operative.

Source: Read Full Article