Food is essential for life—a daily source of calories and comfort. But for the more than 3 million adults in the United States that suffer from Inflammatory Bowel Disease, or IBD, it is also a daily source of pain and discomfort.

Currently, there is no cure for the condition that includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and most people with IBD are diagnosed in their 20s or 30s, meaning a lifetime of symptoms such as diarrhea, gastrointestinal pain, cramping and fatigue.

But new research led by Michigan State University scientists is bringing fresh insight to the IBD table—an unexpected connection between specialized cells in the gut called glia and the genes involved in IBD.

Their findings, published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, could lead to more effective treatments for one of the most elusive gut problems in the world.

“IBD is so complicated—it has a genetic, inflammatory and microbiome component,” said Brian Gulbransen, MSU Foundation Professor in the Department of Physiology and the Neuroscience Program and an author on the paper.

The Gulbransen lab studies enteric glial cells and how they regulate processes in the gut. “Lately researchers have noticed glia have active signaling roles—they talk to other glia, to neurons and to immune cells to regulate homeostasis, like a rheostat that turns neuron activity up or down,” he explained.

Hundreds of millions of neurons line the digestive tract to make the enteric nervous system. It has more neurons than the spinal cord, and the enteric glial cells surround each one. But for a long time, scientists were not excited about glia because they were not excitable cells—electrically speaking.

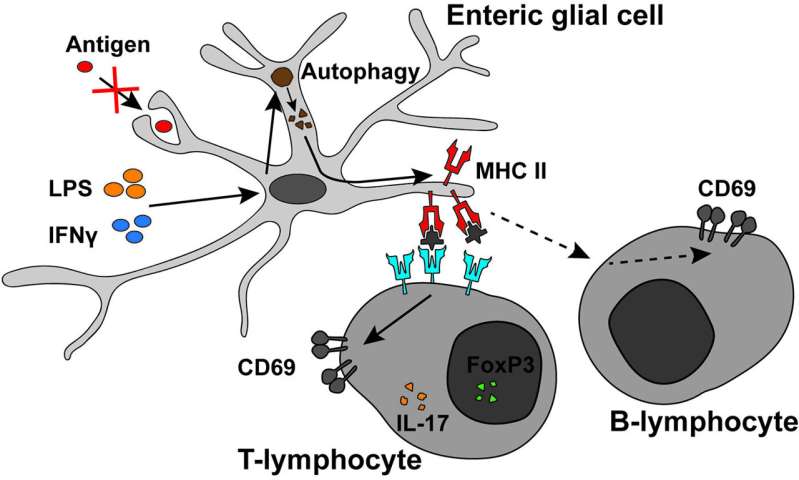

“Once scientists could image other types of activity, they discovered the glia do exhibit forms of fast activity, just in different ways, through a type of firing mediated by calcium that allows them to signal to the neurons,” said Gulbransen, who was just finishing a Ph.D. in neuroscience at the University Of Colorado Hospital in 2007 when new research suggested that glia not only communicated with other cells, but also expressed an antigen known as major histocompatibility complex class II, or MHC-II, in patients with Crohn’s disease.

“There are cells that present antigens such as MHC-II, and glia are one of them, but no one had studied their role in the immune system” Gulbransen explained. “Also, one of the major pathways and genes that are altered in IBD is MHC-II, and antigen presentation has been thought of as a dysfunctional mechanism in people with IBD.”

Aaron Chow, author on the paper and a former Ph.D. student in Gulbransen’s lab now doing clinicals in MSU’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, followed the glia’s gut signals as the foundation of his Ph.D. work.

By comparing genetically modified mice incapable of expressing MHC-II on enteric glia to ones with fully functional expression of MHC-II, Aaron teased out the important function these molecules play. Presence of MHC-II antigens during inflammation triggered the signaling and activation of T- and B-cells that in turn activated immune cell subsets involved in anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Without MHC-II, the immune cells that reduce inflammation were much quieter.

“The takeaway was that a dysfunction in T-cell activation means a person would have more activity towards more bacteria coming across the gut barrier and that drives more inflammation and tissue damage,” Gulbransen said.

The researchers were also interested in how the glia managed to present MHC-II to the body’s immune cells, thereby reducing inflammation around neurons. That led them to another major discovery.

“Since MHC-II molecules are typically expressed as part of the phagocytic pathway responsible for engulfing foreign antigens to present to immune cells, we hypothesized that enteric glia employed similar pathways,” Chow said. “But when they were exposed to fluorescent bacteria that other immune cells readily phagocytose, they refused to engulf these particles.”

Like their unexpected ability to signal to other neurons through calcium instead of electricity, the researchers discovered that the glia also found an unexpected way to drive the expression of MHC-II and communicate with immune cells—autophagy, or the process of a cell eating components of itself. The glia sacrificed their own bodies to protect enteric neurons from inflammation.

“That was really interesting because autophagy is a big pathway that is dysregulated in IBD,” Gulbransen explained. “If these processes don’t work very well, you lose the effective activation of tolerogenic immune cells and get overactivation of the immune system.”

Source: Read Full Article