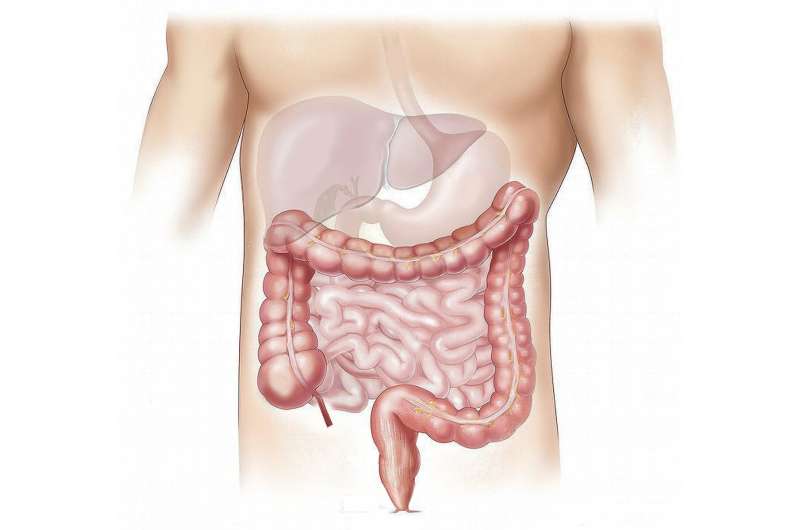

The bacteria living in the intestine consist of some 500 to 1000 different species. They make up what is known as the intestinal flora, which plays a key role in digestion and prevents infections. Unlike pathogens that invade from the outside, they are harmless and tolerated by the immune system. The way in which the human immune system manages to maintain this delicate balance in the intestine largely remains unknown. It is known that type A immunoglobulins, referred to as IgA antibodies, play an important role. These natural defense substances are part of the immune system, and recognize an exogenous pathogen very specifically according to the lock-and-key principle.

A group of researchers led by Dr. Tim Rollenske and Prof. Andrew Macpherson from the Department of BioMedical Research (DBMR) at the University of Bern and the University Hospital for Visceral Surgery and Medicine at the Inselspital have recently been able to show in a mouse model that IgA antibodies specifically limit the fitness of benign bacteria at several levels. This enables the immune system to fine-tune the microbial balance in the intestine. “We have succeeded in demonstrating that the immune system recognizes and restricts these bacteria very specifically,” explains Tim Rollenske, Ph.D., lead author of the study. The results have been published in the journal Nature.

IgA antibodies created in natural form for the first time

IgA antibodies are the most common antibodies in the human immune system, and are secreted by specialist cells in the mucous membranes. They account for two-thirds of human immunoglobulins. Surprisingly, most IgA antibodies produced by the body are directed against benign bacteria in the intestinal flora. Without this immune protection, these microorganisms could also have a detrimental effect on health and cause intestinal diseases. However, the mystery of the way in which IgA antibodies regulate the consensual coexistence in the intestine has remained unsolved.

The reason for this: Until now, studying IgA antibodies in their natural form in animal models was not possible. In their experiment, the researchers led by Tim Rollenske and Andrew Macpherson were able to overcome this hurdle, however. They succeeded in producing a sufficient amount of IgA antibodies specifically directed against a type of Escherichia coli bacteria, a typical intestinal bacterium. The antibodies recognized and bound a building block on the membrane of the microorganisms.

Antibodies impair the fitness of the bacteria

In their experiment, which the researchers worked on for three years, they succeeded in tracking the in-vitro and in-vivo effect in the intestines of germ-free mice with pinpoint accuracy. The antibodies were found to affect the fitness of the bacteria in several ways. The mobility of bacteria was restricted, for example, or they hindered the uptake of sugar building blocks for the metabolism of the bacteria. The effect depended on the surface component that was specifically recognized. “This means that the immune system is apparently able to influence the benign intestinal bacteria through different approaches on a simultaneous basis”, explains Hedda Wardemann of the German Cancer Research Center, co-author. The researchers therefore speak of IgA parallelism.

Source: Read Full Article