The terminology humans have conceived to explain and study our own brain may be mis-aligned with how these constructs are actually represented in nature. For example, in many human societies, when a baby is born either a “male” or a “female” box is checked on the birth certificate. Reality, however, may be less black and white. In fact, the assumption of dichotomic differences between only two sex/gender categories may be at odds with our endeavors that try to carve nature at its joints. Such is the case with a new paper, published recently in the journal Cerebral Cortex, where researchers argue that there are at least nine directions of brain-gender variation.

Many classical statistical approaches pre-assume which groups they expect to see in the data; such as old vs. young participants, or introverted vs. extroverted participants. Everything else that follows after that critically depends on the initial decision of assigning individuals into strict groups. In this new study, the researchers did not pre-assume what the brain gender groups, transcending male, female, and individuals in-between, should be. Instead, they derived the brain-gender groups directly from brain-imaging and psychological assessment items in an agnostic data-driven fashion.

“Our goal was to demonstrate that widely available brain-imaging methods are capable of providing evidence against a strict binary view of how sex/gender is manifested in the brain,” explains Dr. Danilo Bzdok, Associate Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine and a senior author on the paper. “These findings have important consequences for the movement towards improved equity, diversity, and inclusion in Canada and other countries. By raising awareness from the biological perspective we may contribute to building a society where individuals identifying themselves in between the labels of male and female do feel included rather than discriminated against.”

Pulling the data together

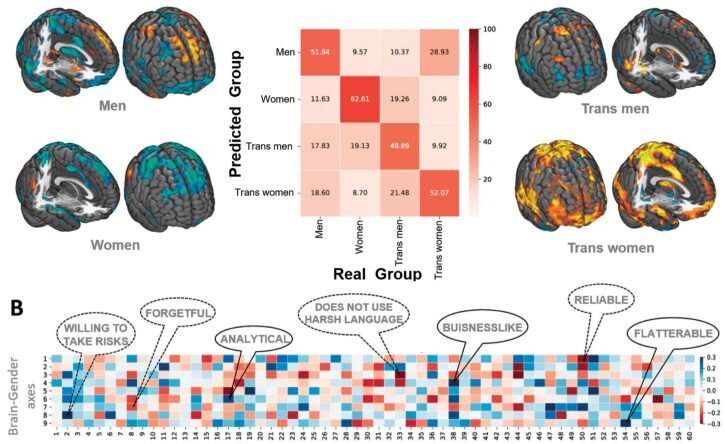

In order to conduct their study, the researchers acquired a unique dataset comprised of individuals of wide sex/gender diversity. Rather than only studying gender behavior in a male and a female group, as is commonly done, they acquired a rich sample that also included individuals that underwent sex transformation from male to female as well as individuals that have undergone sex transformation from female to male. The measured brain connectivity fingerprints of these four groups were then related to a comprehensive profile of gender-stereotypical behavioral traits, working closely with Professor Ute Habel and Dr. Benjamin Clemens at the Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, RWTH Aachen University.

The researchers used machine learning algorithms that could provide evidence that sex/gender may not be a dichotomic entity in the human brain. In an unbiased pattern-learning approach they could show that at least nine dimensions of brain-gender variation can be robustly identified. That is, the particular individuals can be assigned to nine “expressions” or coordinate system axes of how much they fall along a particular distribution of brain-gender variation.

“My lab works at the interface between systems neuroscience and tailoring machine-learning algorithms to answer questions in large neuroscience datasets,” says Dr. Bzdok, who recently moved to Montreal to join the McGill community. “Montreal has the advantage of combining world-class neuroscience institutions, such as The Neuro, with top-notch Artificial Intelligence institutions, such as the Mila Quebec AI Institute, in the same city. In both of these research areas, there is a lot of legacy and, now, momentum to build a critical mass to promote forward progress. As such, Montreal is a particularly promising place that is likely to make important contributions to bridging neuroscience and AI.”

Moving the research forward

Dr. Bzdok is optimistic that budding clinical consortium initiatives will allow them to pool even richer and multi-modal datasets to acknowledge even more facets of sex/gender variation existing in the wider population. From a data analytics standpoint, he explains that the more data we can gather, the more likely it is that we will discover a greater number of sex/gender dimensions.

Source: Read Full Article