Pain management in the United States is inequitable, with Black people often receiving less aggressive and less accurate pain treatment than White people. New research in Social Psychological and Personality Science (SPPS) has identified a possible cause of this disparity, reporting that medical providers are better at discerning real from fake pain expressions for White people than Black people.

Previous studies have investigated prejudice, false stereotypes, and empathy deficits as contributors to Black people receiving less-intensive pain treatments than White people. However, the new research, led by E. Paige Lloyd of the University of Denver, also demonstrates that participants recommended more accurate care for White people than Black people.

“We argue this sensitivity deficit could be a contributing factor in racial disparities in pain care,” says Dr. Lloyd. “Science that identifies processes underlying disparate care opens the door for evidence-based interventions and thereby more equitable healthcare.”

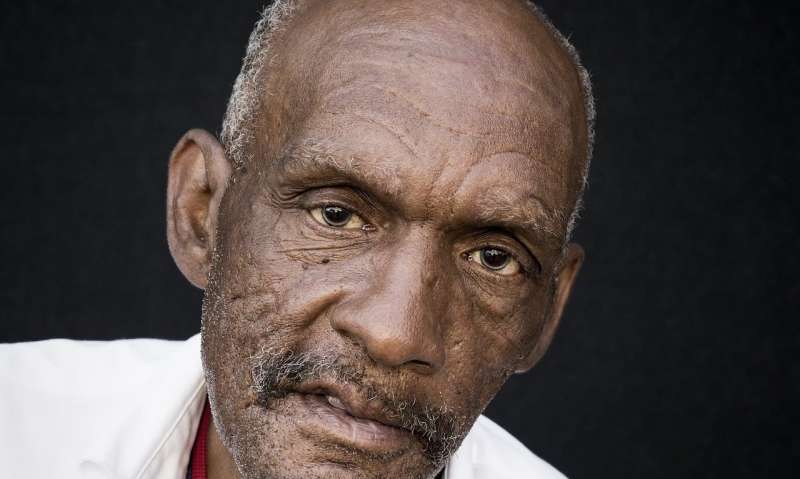

The research included 904 participants, including laypeople and medical providers, across six studies. In four studies, participants were shown videos of White and Black people expressing real and feigned physical pain. They were then asked to discern whether each expression of pain was real or fake. Both White and Black participants were better at discerning real expressions of pain from fake in White people than in Black people.

In a subsequent study, participants were asked to recommend treatment for the people who had expressed real and fake pain. White people were recommended greater treatment when they expressed real pain, relative to fake pain, whereas treatment recommendations for Black people did not differ between genuine and fake displays of pain. This demonstrates that White people received more accurate treatment recommendations based on their actual pain experiences than Black people.

“Our findings indicate that Black Americans are not just undertreated for pain, they may also receive pain treatment less calibrated to their needs,” Dr. Lloyd explains.

Researchers also warn that the implications of these failures in pain detection could extend far beyond a hospital or doctor’s office. A caregiver may fail to address a child’s genuine medical condition, a referee could ignore a truly injured player, or a judge might fail to validate a victim suffering from actual distress.

Future research, Dr. Lloyd says, would do well to move beyond the lab and focus on medical settings. Examining possible intervention strategies is also an important next step. While current interventions focus on reducing bias, Dr. Lloyd notes that they are unlikely to improve doctors’ ability to discern authentic pain in Black patients and treat it accurately.

Source: Read Full Article