A big study to help Medicare officials decide whether to start covering brain scans to check for Alzheimer’s disease missed its goals for curbing health care costs, calling into question whether the pricey tests are worth it.

The results announced Thursday are from a $100 million study of more than 25,000 Medicare recipients. It’s been closely watched by private insurers too, as the elderly population grows and more develop this most common form of dementia, which currently has no cure.

Advocates for coverage say they hope to persuade the agency that the scans still offer benefits even if they don’t save much or any money. An accurate diagnosis helps families plan for the future even if the course of the disease can’t be changed, said Dr. Gil Rabinovici of the University of California, San Francisco.

He led the study and gave results at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference taking place online because of the coronavirus pandemic. They have not been published or reviewed by other scientists yet.

A spokesman for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services said the agency considers all information on risks and benefits, and that a formal request would need to be filed to prompt reconsideration of its 2013 decision to not cover the scans except in research and special circumstances.

More than 5 million people in the United States and millions more worldwide have Alzheimer’s. The only sure way to diagnose it used to be checking the brain after death.

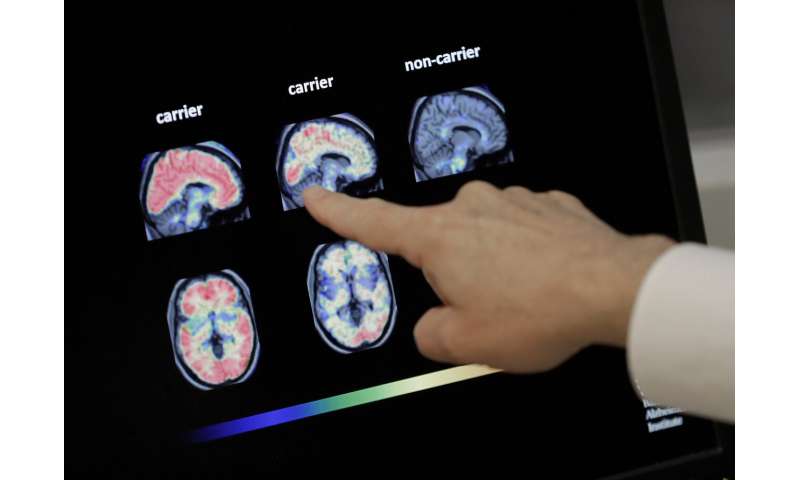

Recently, PET brain scans have been developed to detect signs in living patients. But they cost $4,000 to $5,000 and insurers haven’t covered them because it’s not known if they have benefits.

The study aimed to find out. It involved 12,684 people with dementia or a less severe condition called mild cognitive impairment, or MCI. They were given scans and compared to Medicare recipients who were similar in age, sex and other factors but not given scans.

Partial results from the first 4,000 participants a few years ago suggested the scans more accurately diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease and altered counseling or care in up to 60% of cases.

This part of the study examined whether the scans save money by reducing hospitalizations and emergency room visits. These are high among people with dementia because their confusion may lead them to take too much or skip medicines, or to wake in the night and fall and break a bone. The theory: If a scan reveals someone has Alzheimer’s, caregivers can put a plan in place to prevent such problems.

The study missed its goal of curbing hospitalizations by 10% in the year after the scan: Rates were 24% among those scanned versus 25% of the others.

However, among those scanned, there were fewer hospitalizations for those with Alzheimer’s versus those without the disease.

That result suggests caregivers “weren’t panicking” when they saw symptoms that could be due to Alzheimer’s and didn’t rush to the hospital, said Maria Carrillo, the Alzheimer’s Association’s chief science officer.

The association sponsored the study with the American College of Radiology and several imaging companies. Medicare officials helped design it and paid for the scans. Rabinovici is a paid adviser to several companies developing Alzheimer’s treatments or diagnostics.

Dr. Suzanne Schindler, a neurologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, who enrolled patients in the study, said that with no treatment to alter the course of the disease, “it’s a very fair question—why should we even do this testing?”

But patients and families want an accurate diagnosis to make big life decisions such as moving, retiring or redoing finances, she said.

That was the case for Keith Szolga, whose 83-year-old mother, Beverly Szolga, had a scan in the study at Washington University. Doctors had ruled out some other possible causes for her growing confusion and the scan showed Alzheimer’s.

After getting the results, “I don’t think that we did much of anything differently other than we no longer let her drive,” he said. “It gives family members peace of mind to know” what they’re up against.

Dr. Howard Fillit, chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, which had no role in the study, sees value in the scans.

“If it was any other disease, people would want a specific diagnosis” and the scans give that, he said.

Source: Read Full Article