Prostate cancer has long held an infamous reputation as a notable killer of Black men—a malignant stalker that has caused one of the deepest disparities in survival among all cancers affecting males.

New research from Stony Brook Medicine, the health and medical science enterprise of Stony Brook University in New York, has analyzed reasons for the stark racial survival differences for this form of cancer. The research, published in the journal Cancers, challenges the long-standing view that Black men may be biologically prone to prostate cancer.

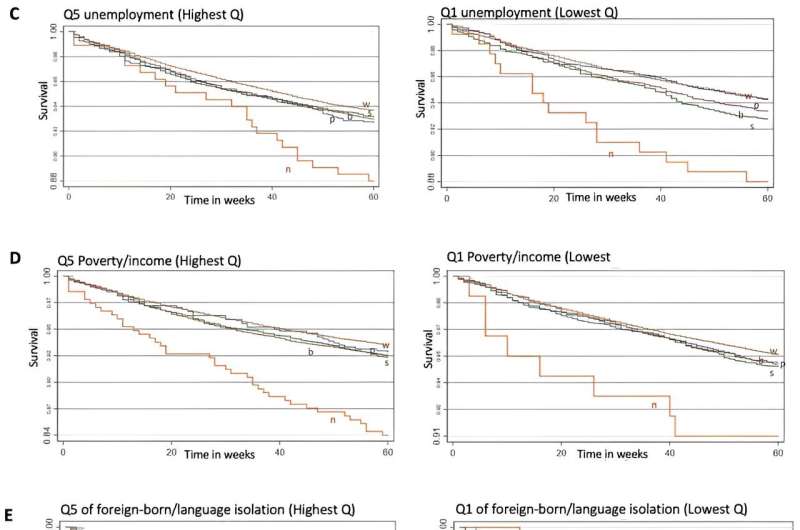

The epidemiological study found that most of the disparity in prostate cancer survival between Black and White men—nearly 75%—could be attributed to modifiable risk factors, such as later diagnosis, absence of health insurance or even differences in access to cancer screening.

“We studied incidence and survival for prostate cancer among men of varying racial and ethnic backgrounds,” Dr. Sean Clouston, senior author of the new research told Medical Xpress. “We initially found that incidence was higher in men from historically underserved backgrounds, while survival was lower in the same populations.”

“Next, we accounted for various social and clinical measures including health insurance status and severity of disease at the time of diagnosis. These factors explained much of the disparity,” Clouston added, noting that “lacking health insurance was associated with both being from a disadvantaged background and having a more severe cancer at diagnosis and this explained the higher risk of death.”

Clouston, an epidemiologist in Stony Brook’s Department of Family Population and Preventive Medicine, notes that his team’s new research should prompt other research teams to explore similar questions to find additional reasons why a disparity persists.

The findings stem from a survey and statistical analysis of nearly 240,000 prostate cancer patients and their 5-year survival rates. The vast majority of men—94%—whose cases were analyzed in the study survived five years. But poverty and lower educational attainment were nevertheless associated with more severe disease outcomes and death.

For years it has been taken as a given that prostate cancer in Black men develops more aggressively and that this feature alone explained the difference between Black and White survival. Yet Clouston said his team’s data “are not strongly supportive of this assertion.”

“First, access to insurance is a substantial predictor of prostate cancer survival. This shouldn’t be the case if it were simply that cancers were more severe,” Clouston underscored. “Second, the severity at initial diagnosis is actually pretty similar between races and ethnicities as are other markers of severity including, for example, whether the cancer is localized or not. Still, the risk of mortality after diagnosis differs for Black versus White men.”

Despite the new findings, numerous patient advocacy organizations underscore that prostate cancer is more prevalent among Black men, a factor that underlies lower survival and cancers that are generally more difficult to treat. The American Cancer Society, for example, reports that the incidence of prostate cancer is 70% higher in Black men compared with their White counterparts.

And the patient advocacy organization, ZERO Prostate Cancer, asserts that 1 in 6 Black men will develop prostate cancer in his lifetime compared with 1 in 8 men overall. The group further states that Black men are 1.7 times more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer and 2.1 times more likely to die of the malignancy than White men.

“We looked at a population registry that included details on prostate cancer incidence, clinical severity, and survival across a range of years,” Clouston explained, underscoring that the research involved a large sample—239,613—cases of prostate cancer in the United States involving a variety of regions throughout the country.

“We examined survival over five years after initial diagnosis,” the epidemiologist said. “The vast majority of men survived five years, more than 90%, so this study could only be done because we had a large database.”

Cases were drawn from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program, also known as the SEER database. Meanwhile, Clouston said, the Stony Brook team’s findings pave the way to new avenues of research as medical experts begin the arduous task of crafting policies to help alleviate deeply persistent cancer disparities.

Clouston noted that his team’s findings call for tailored interventions to address these differences. “Public health initiatives to decipher socioeconomic issues related to prostate cancer disparities, such as screening access and availability of the best treatments, will further inform communities on how to reduce prostate cancer risk.”

“Prostate cancer is a highly treatable disease,” Clouston said, adding that men “should be surviving at high rates. Unfortunately, there are a lot of barriers to care that can cause even a treatable disease to cause inequalities. In the future, we hope that more efforts will be made to improve survival for highly preventable diseases.”

More information:

Christiane J. El Khoury et al, Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Prostate Cancer 5-Year Survival: The Role of Health-Care Access and Disease Severity, Cancers (2023). DOI: 10.3390/cancers15174284

Journal information:

Cancers

Source: Read Full Article