A tumor is often made up of different cells, some of which have changed—or evolved—over time and gained the ability to grow faster, survive longer and potentially avoid treatment. These cells, which have an “evolutionary advantage,” are thought to cause the vast majority of cancer deaths but researchers now have a new tool to tackle tumor evolution: TrackSig.

TrackSig—which was developed by Quaid Morris, a professor of computer science and molecular genetics at the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, and his team at the Vector Institute and OICR—is a novel computational method that can map a cancer’s evolutionary history from a single patient sample and in turn help researchers thwart the disease’s next move.

“We combined sequencing with evolutionary theory and mathematical modeling to understand how cancers develop and adapt to resist treatment,” says Yulia Rubanova, Ph.D. Candidate in the Morris Lab and lead author of the study. “This understanding lays the foundation for us to be able to predict—and impede—tumor evolution in future cancer patients.”

TrackSig was published today in Nature Communications alongside nearly two dozen other publications in Nature and its affiliated journals related to the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Project, also known as the Pan-Cancer Project or PCAWG.

“The tools and findings from the Pan-Cancer Project are changing the way we think about cancer,” says Morris. “We’ve uncovered new opportunities to improve diagnosis and treatment, and we’ll continue to strive towards getting the best treatment to patients at the right time.”

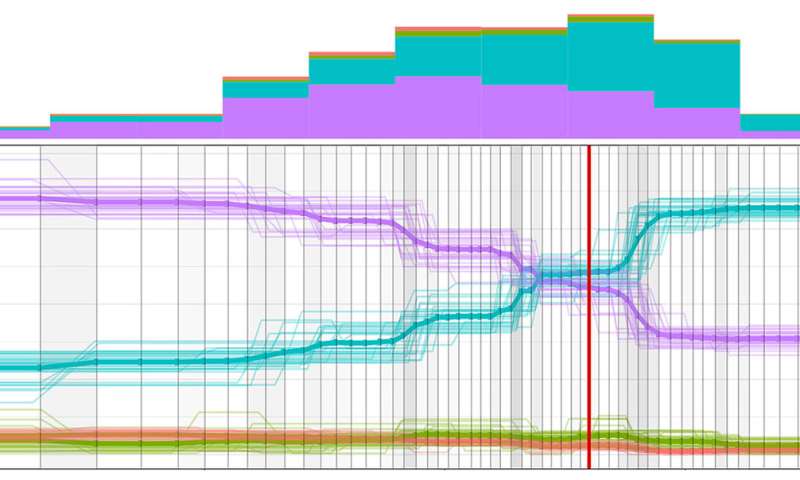

Previous tumor evolution studies focused on identifying the most frequent changes—or mutations—in a patient sample, where the most common mutations represent changes that came earlier in the tumor’s development and less common mutations represent more recent changes. Instead, Morris’ TrackSig charts different types of mutations over time, generating maps of a tumor’s evolutionary history in finer detail and with better accuracy than ever before.

This level of resolution enabled the discovery that many cancer-causing genetic changes occur long before the disease is diagnosed.

“For exceptional cases like in certain ovarian cancers, we were able to see these early events happening 10 to 20 years before the patient has any symptoms,” says Lincoln Stein, Head of Adaptive Oncology at OICR and member of the Pan-Cancer Project Steering Committee. “This opens up a much larger window of opportunity for earlier detection and treatment than we thought possible.”

Source: Read Full Article